After hiking the Halemau’u trail last June, I decided I wanted to hike through the whole crater from the peak and come back up on Halemau’u.

Last Sunday was the day. Trisha dropped me off at the peak of Haleakalā and I went on the approximately 12 mile hike, first descending from 10,000 feet down into the crater floor which is in the 6,500 to 7,500 foot range. At the end, of course, I would need to climb back out the 1,300 elevation change of the Halemau’u trail, ending back up at the trailhead at around 8,000 feet.

Here is the map of my hike. the green bubble is the starting point at the peak. The red bubble shows the Halemau’u trailhead.

Here I am at 9:00 am. It was cold (in the 50ies) and raining when I left. I am just outside the ranger station at the top, pointing down into the crater. I am ready to go.

Here is a view of the crater wall looking south. I’ll be going down the red slope in the background.

Right by the parking lot is the trailhead. In the background you can see the antennas and telescopes on the summit ridge. The U. S. Air Force operates the 3.6-meter, 75-ton Advanced Electro-Optical System, or AEOS, telescope on the summit of Haleakalā. It is the largest optical telescope in the Department of Defense.

The trail leads down the sandy slopes of the inner crater rim.

Without any vegetation at this altitude, you can see the trail stretching ahead for miles.

Here is a view north generally in the direction where I’ll be going. See the green slopes in the center of the picture? Those will be visible in other pictures later when I am behind those, looking back up. In the far distance, if it were not cloudy, we’d be able to see the ocean far below. But not on this day.

Here is my first look back up. You can see the building from where I stood in the first photograph above, pointing down.

Massive walls of rock form the inner rim. The trail ranges from course sand to sharp rock.

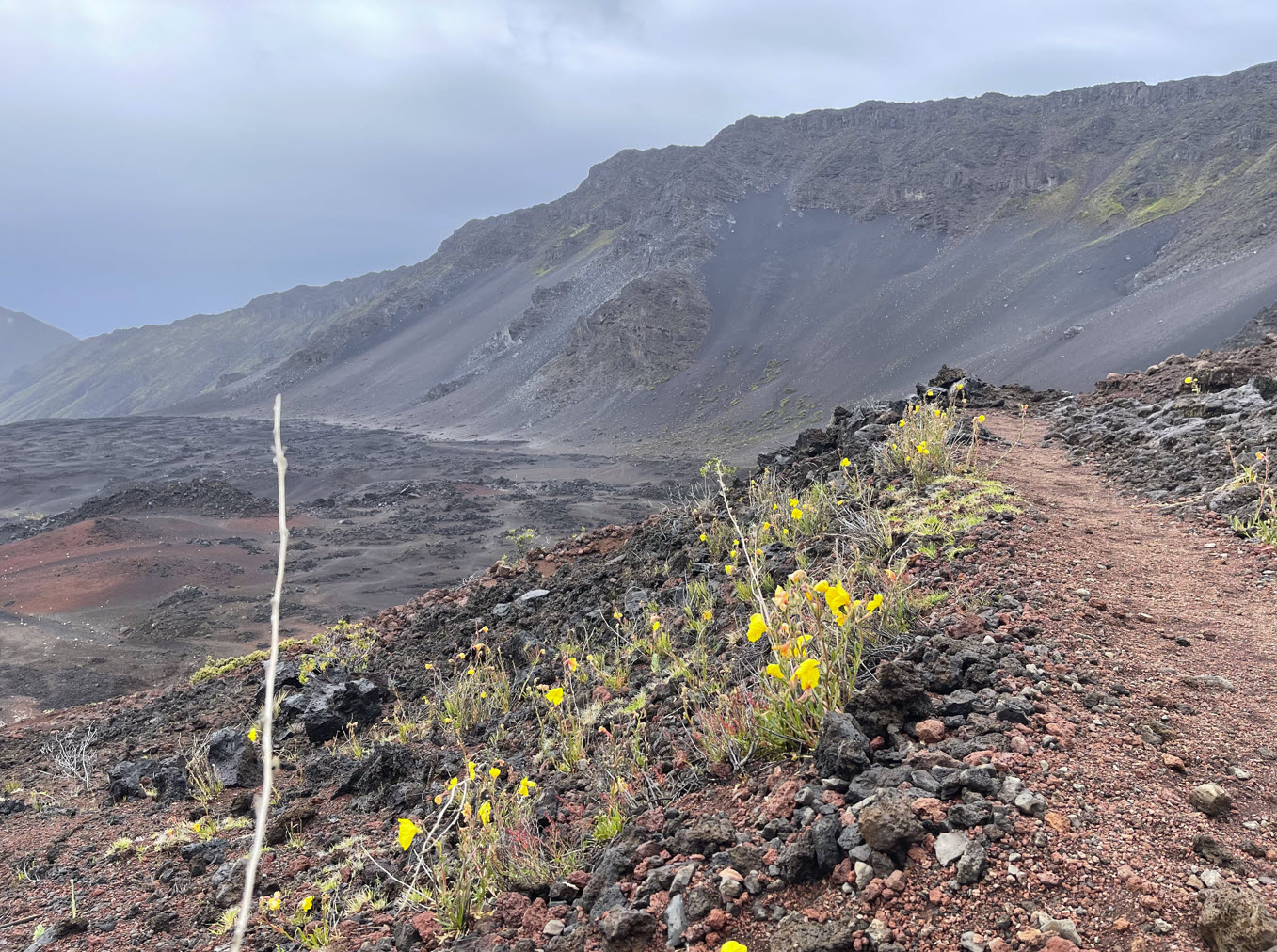

Beautiful yellow flowers seem to cling to life at this unforgiving altitude. They are called the evening primrose (oenothera biennia), which is a non-native species that seems to thrive in the harsh conditions high on the volcano.

The bright yellow flower can be seen along park roads and trails in the crater. It is native to eastern and central North America, where it is part of an ecosystem that helps to control it. In Haleakalā National Park, resource managers work hard to contain these and other invasives that are free from their natural controls.

The Haleakalā silversword is a strikingly beautiful plant which is only found on the island of Maui at elevations above 6,900 feet on the summit depression, the rim summits, and surrounding slopes of the Haleakalā crater. It has been a threatened species since it was classified on May 15, 1992. Prior to that time, excessive grazing by cattle and goats, and vandalism inflicted by people in the 1920s, had caused its near extinction. Since strict monitoring and governmental protection took effect, the species’ recovery is considered a successful conservation story.

After the silversword blooms, the leaves die and form a cone on the bottom of the plant.

Here is my first look back up to the rim. The red arrow points to the ranger building, which is almost no longer discernible from this distance.

After about four miles I reached the crater floor at about 7,500 feet. I needed some rest. Immediately, these birds came up and walked right up and looked at me. Obviously, they had learned that people liked to feed birds. They were fearless.

I had to look them up: Introduced from Eurasia, the sandy-brown Chukar is a game bird that lives in high desert plains of western North America, as well as in Hawaii and New Zealand.

Here they are picking the crumbs I let them have.

Turning away from the birds and looking north, this was my view. In the distance on the red slopes you can see the thin faint line that is my trail.

Along this trail I came to a garden of silversword. It looked like an alien landscape. I could imagine some arachnoid alien coming toward me down the trail and I would not have been surprised.

Another look back across the crater floor to the rim in the west from where I came. The red arrow again points to the location of the ranger station. If I didn’t point it out it would not even be visible any more from this distance. As in all the photos, you can click on the picture and then zoom in.

The evening primrose seems to grow right out of the sheer volcanic rock, almost like a miracle.

Looking toward the north and down, this is where I am going. The slope in the back is where I will have to climb out of the crater once I get there.

Along the way there are sometimes very strange lava formations. This is a little cave large enough so I could stand in it with a window on the other side.

And always, in all directions, I saw course sandy slopes that looked smooth from a distance but are often just millions of sharp volcanic rocks. The green spots on the rim are those that I pointed out at the beginning of this post, when I looked down on them from the distant rim behind.

Here is another shot of the ranger station at the red arrow and the green slopes.

The stark, alien beauty of the Haleakalā crater is embodied in this photograph, with the lone flower in the foreground and the harsh environment it lives in.

Finally I am getting close to the other side. If you zoom in on the picture above, around where the red arrow is, you see the faint lines that are the switchbacks of the trail where I’ll be climbing out.

Before the climb, however, I took a rest stop at the Holua cabin and the little campground around it. There was nobody there.

Did I mention that on the entire trip so far I had encountered no more than perhaps five people in two groups? There was nobody on that side of the mountain. I saw some groups of casual hikers coming down and going up the Halemau’u slope, but that was the extent of other people.

The terrain on the way up along the switchbacks is very different. There is dense vegetation. It was raining lightly, and quick cold with stiff winds.

More views of the trails on the switchbacks up.

The park service installed fences to keep out goats and pigs, and keep people from falling down steep cliffs.

I am on the northside of the mountain, and I can get glimpses of the valley below.

Finally, after 12 miles of hiking, and a steep ascent for the last mile and a half, I saw the parking lot in the distance, where Trisha waited for me with the car.

Here I am at the car, looking east for a parting shot, with the Pacific ocean 8,000 feet below. It’s about 3:00 pm. The full hike took me about six hours.

I think next year I’ll do the same trek, but the other way around. That will mean rather than dropping 2,000 feet, I’ll be climbing 2,000 feet. It’ll be a little slower.

I am already excited about it.

wow — but better you than me. But I liked the views and comments. I’m surprised you went alone. It’s good to know there are such “unsullied” outbacks, tho. The earth is so varied! I assume the crater is an ancient volcano.

The entire island of Maui is a volcano. It was formed about 1.5 million years ago. Haleakala last erupted in 1790. I love to hike alone. That’s how I clear my head.